J/e is the symbol of the lived, rending experience which is m/y writing, of this cutting in two which throughout literature is an exercise of the language which does not constitute m/e as subject. J/e poses the ideological and historic question of feminine subjects.

- – Monique Wittig

Monique Wittig’s The Lesbian Body describes a fictional culture of women who are simultaneously each other’s lovers and assailants. The text continuously illustrates their rending expressions of love via corporal invasion and dismemberment, and in kind, it employs a slash in the “I” Wittig alludes to above. In the original French, je becomes j/e. In translation, the I cannot be split, so it is italicized, and the slash appears instead in m/e and m/y. The graphic sum of these marks throughout the text is a conflation of the slash and the I, such that the I itself begins to enact a split. I’m interested in the split subjectivity that Wittig proposes, not only vis à vis the confusion of self and other, or interior and exterior selves, but the possibility that by inevitably failing to elucidate selfhood and identity, language itself engenders a split between the mind and the subject’s context in the world.

My recent wool paintings use this I / as their guiding structure. These works are made from off-white blankets - they resemble raw canvas - that I dye, cut, sew, and reconfigure into new compositions, often flipping the right triangles in each of the blankets’ corners, thus scrambling the original “front” and “back” of each piece. Before I cut the wool, the dye patterns resemble abstract typographical marks, composed of smoky bars that create secondary color fields where they overlap. Once it is cut, the central figure in each composition is a right-slanting diagonal bar: the I or the slash.

There are numerous boundaries at play in these works, whose articulation depends upon cuts that are also sites of attachment. Etymologically, articulation refers to a connection – a joint – that also implies speech. The different spaces in the paintings are articulated to each other by virtue of splits that both divide the field and construct new relationships. The central slash directly evokes the cuts made in the original fabric of the work, necessary for its restructuring. Yet the slash is not quite a typographical mark, because it is also the literal body of the canvas, itself defined by cuts, seams and the edge of the stretcher (around which the fabric suggestively continues). This slash as body reminds us that outlines around things are constructions. Incongruous abutting stains - not painted marks - indicate the harder-edged divisions here, but what reads as line is in fact the slight shadow cast by the ridge of the seam. This shadow alludes to the inside of the canvas, where the cut edge of the fabric and the thread line are actually visible. The seam also marks a displacement of material to the inside of the painting. We don’t have access to this interior, but the notion of an obverse is called into question by the continuous circulation of the edges of the fabric to the interior via the seams.

In many ways, these works invert the conventional process of making a painting. They appear when they are - finally - stretched. Operating with a stretcher, these sewn compositions both omit material and pull apart, yielding a tight vulnerability that clarifies the limits at play in the work. They confuse image and object: by flipping the cut pieces in search of new forms, the work fails the conceit that painting is anchored in two dimensions. The seams introduce hard lines amidst the hazy boundaries of the dye, facilitating jarring near-misses as each colored field attempts to re-register itself with its original whole. The straight edges punctuating the blurry dye lines sever and torque the color fields and negative space into new patterns, figuring marching triangular flags, crude limbs, and even guns. The final images of these paintings adhere to a logic that is absent in the original dye pattern. Their two sides are irreconcilably scrambled, with no ground to identify the posteriors and anteriors of each initial composition. They are redirections of other images, and they remain indeterminate by refusing to settle down.

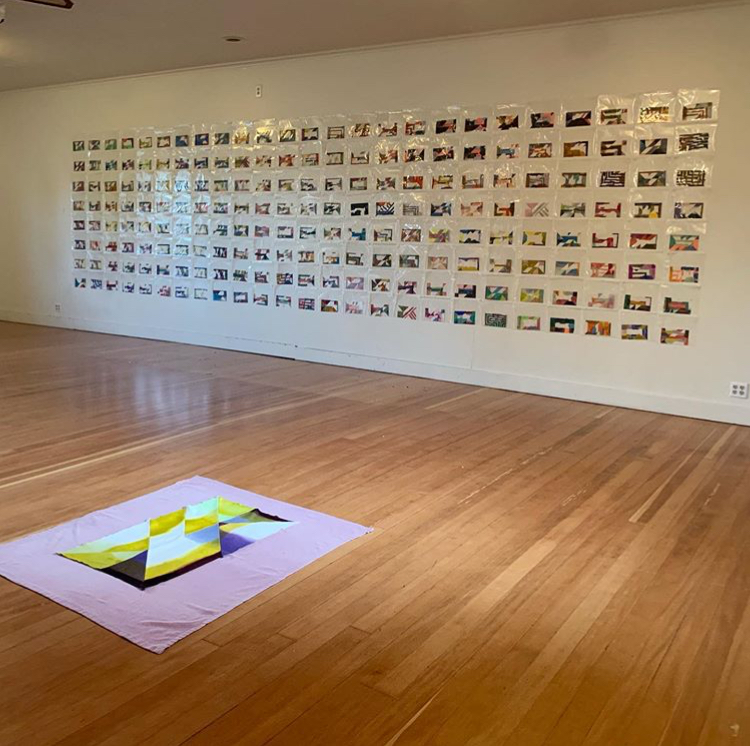

Picking up the task of translation between paper and fabric, the collages on view in new wool/drawings start to articulate the potential of this procedure. Painted on slips of transparent paper, they begin as colored bands rendered in one of several basic configurations – much like the pieces of dyed wool – that contract sets of secondary colors where the bands meet. Their compositions emerge not by way of gestural marks, but via their italicization. The substructure of cuts that drives the system describes a diagonal “I” shape, but unveiling this I depends on the re-arrangement of the cut pieces of paper, which induces new juxtapositions between the ground, the primary colored bands and secondary colored joints. This scrambling reveals each collage as a flat knot of potential energy, neighboring dozens of alternate constructions, each inextricably bound with the substructural I.